As this is the first post about data warehousing stuff I thought we might start with something simple: the date dimension.

In a time when a lot of organisations are talking about big data, predictive analytics, no-SQL data stores and huge hadoop clusters one might think the basic stuff is well covered. It’s known territory, there’s nothing new to discover there.

However, even the most basic of things are sometimes weirdly wrong in a lot of places. Case in point: the date dimension.

I’ve seen quite a few data warehouses and all of them have a date dimension. It’s probably the most used dimension in any data warehouse. And yet, in almost all of them things are just… wrong.

How can a date dimension be wrong? It’s just a set of columns with years, month names and numbers, days of the month, anybody can calculate those for any day, it’s quite trivial, isn’t it? Well, yes and no. The problem usually is around weeks.

If the typical year-quarter-month-day hierarchy has no big secrets around it (although I’ve seen a few date dimensions with no mention to month numbers and so months are sorted April-August-December-…), weeks cause all sorts of odd things in reports.

Case 1: weeks as children of Months

I’ve seen a few examples where a date hierarchy would look like this: Year-Quarter-Month-Week-Day. Obviously, as months are very badly behaved and don’t have an integer number of weeks, this causes some weeks to break around month boundaries. You get Week 31, child of July, with 4 days (28, 29, 30 and 31 of July) and Week 31, child of August, with 3 days (August 1, 2 and 3). Called me old fashioned, but I like weeks to be 7 days long.

This type of hierarchy is obviously wrong, but it’s also easy to fix. Just use two different hiearchies, one Year-Quarter-Month-Day and another one Year-Week-Day of Week-Day. Weeks do not fit into Months and as such should not be in the same hierarchy. And most date dimensions I’ve seen, apart a few exceptions, do have this in mind.

Case 2: getting the years wrong

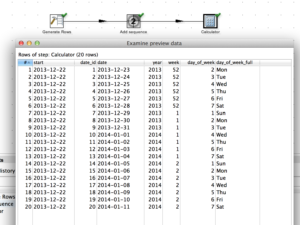

However, the most common error I’ve encountered is more subtle. Let’s first use the naive approach and see where it takes us. A simple PDI transformation generates 10 rows and calculates dates between 2013-12-23 and 2014-01-11. I chose these limits because they’re both more than 1 week apart from the year change. The calculator step is calculating the year, week number and day of week of the date. I also calculate the day of the week in English because I want to know what does DOW=1 mean and I never know from memory.

When we preview the data we notice immediately two things: 1) weeks start on Sunday (ok, it’s a convention I can live with) and 2) 2013-12-29, 2013-12-30 and 2013-12-31 are in week 1… of 2013?

This can’t be right, can it? If 2013-12-31 belongs to week 1, as does 2013-01-01, that means we have this weird week 1 of 2013 that has some days in January and some more in December. Which doesn’t make any sense. Even worse, if we repeat the exercise for end of 2012, beginning of 2013, we see that there are 5 days in January 2013 that belong to week 1. These 5 days, together with 3 days in December give us a very weird W1 of 2013 with 8 days, which are divided in to two groups very far apart from each other.

But, believe it or not, I’ve seen something like this in a lot of production dim_date tables and the users’ reaction was more a “meh, we know our data never makes sense around the end of the year, we live with it” than a “this is obviously wrong, fix it!”. This was a production data warehouse that was used everyday by senior level executives to get numbers out and evaluate the company performance and there’s a 2 week period every year for which the data is uterly useless and completely wrong!

Call me old fashioned, but for me a week should have the following two basic properties:

1) it must have 7 days. Always.

2) they must be 7 consecutive days.

On top of that, if possible, I’d like it to:

3) always start in the same day of the week

and 4) sorting within a week must match the chronological sorting of dates.

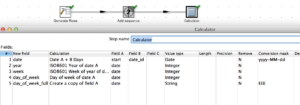

So clearly we have a problem here. Looking at the calculator step and the options available (btw, someone should sort those, it’s getting harder to find a specific calculation with every new version of PDI), there’s an interesting option immediately after the Week of Date A: the ISO8601 Week of Year of date A. And also ISO8601 Year of date A.

The wikipedia article explains quite well what the definition is and how to implement it (my favourite definition, because it’s also the easiest to actually implement in an algorithm: week 1 is the week of January 4th). So, there’s a standard for calculating week numbers, lets use it! But, while reading it, it becomes clear that the year cannot be the calendar year. It may happen that January 1st belongs to week 52 of the previous year (e.g., 2012-01-01 belongs to Week 52 of 2011) or even week 53 of the previous year (2010-01-01 belongs to week 1 of 2009). Likewise, December 31 may belong to week 1 of the following year, as was the case with 2013-12-31.

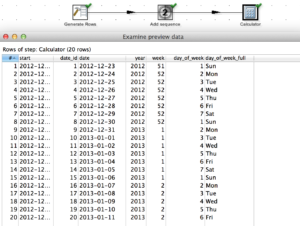

So, lets give it another go and calculate week numbers and years by the ISO 8601 standard.

Ok, now it makes sense. Just one thing, though: ISO weeks start on Mondays and days of week return 1 for Sundays. So we can’t use the Day of week calculation to give us an ordinal column.

Two options there:

a) Map Mondays to 1, Tuesdays to 2, …, Sundays to 7

b) Just replace all 1 for Sundays by 8 if you’re feeling lazy.

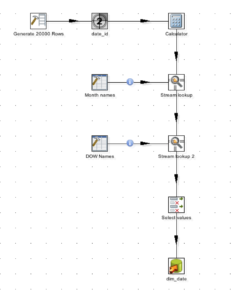

Now we can calculate a proper date dimension using PDI, one that doesn’t blow up when users query the week over week growth of sales around New Year.

You can download the transformation here: dim_date.ktr.

And this is what the Mondrian hierarchy looks like:

<Dimension type="TimeDimension" visible="true" highCardinality="false" name="Dates">

<Hierarchy name="By Month" visible="true" hasAll="true" allMemberName="All" primaryKey="date_id">

<Table name="dim_date">

</Table>

<Level name="Year" visible="true" column="year" type="Integer" uniqueMembers="true" levelType="TimeYears">

</Level>

<Level name="Month" visible="true" column="month_name_full" ordinalColumn="month_number" type="String" uniqueMembers="false" levelType="TimeMonths">

</Level>

<Level name="Day" visible="true" column="day_of_month" type="Integer" uniqueMembers="false" levelType="TimeDays">

</Level>

<Level name="Date" visible="true" column="date_string" type="String" uniqueMembers="true" levelType="TimeDays">

</Level>

</Hierarchy>

<Hierarchy name="By Week" visible="true" hasAll="true" allMemberName="All" primaryKey="date_id">

<Table name="dim_date">

</Table>

<Level name="Year" visible="true" column="iso_year_of_week" type="Integer" uniqueMembers="true" levelType="TimeYears">

</Level>

<Level name="Week" visible="true" column="iso_week_of_year" type="Integer" uniqueMembers="false" levelType="TimeWeeks">

</Level>

<Level name="Day of Week" visible="true" column="day_of_week_full" type="String" ordinalColumn="day_of_week_ordinal" uniqueMembers="false" levelType="TimeDays">

</Level>

<Level name="Date" visible="true" column="date_string" type="String" uniqueMembers="true" levelType="TimeDays">

</Level>

</Hierarchy>

</Dimension>

Of course a lot more tweaks can be added to this date dimension, suggestions as to how to improve it are welcome.

Back to blog

Back to blog

2 Comments

Thanks Nelson , you’re the MasterMind

Hello,

nice article.

from my expirience the best way to deal with a date dimension is to bring it from outsource

like : http://www.ipcdesigns.com/dim_date/index.html#tabledef

its a ready made dim_date .

at my project i just pick the columns relevant for the scenario ,

also i use a “where” to take only the dates i need to the BI tool

for example : 3 dynamic years.

sometimes we need the future too : due dates, future meetings , predictive…

it has also the weekends, holidays , last day of months…

lets say we have enough ETL’s to develop with out this part